In the visit to the saruthi planet there’s great material for a go-getting young television director with a CGI budget to really fuck with some perspective and create an unsettling, discordant visual world. There’s a lot to like in the novel from an adaptation standpoint - quite a few setpieces, quite a few big meetings and summits where you can just hire respected British character actors and tell them to work broad to play, oh, Schongard or Molitor or Endor or Voke. Our hero falls in the middle of both traditions - quite a both-sides centrist fellow - and spends the novel outing a decadent aristocratic merchant clan that has fallen to Chaos and then chasing it halfway across the sector to deliver judgment. There are two factions presented in the Inquisition, the orthodox conservatives which purge heresy the moment they see it (and accordingly are all assholes) and the radical heterodoxes who think the Inquisition should keep an open mind (and accordingly always support doing stupid and reckless things). Our hero Inquisitor Eisenhorn needs to suss it out. There’s heresy and Chaos building in the hideous ranks of man. We’ll begin with Xenos, which would likely form the basis for any self-respecting season one of this show. The verdict is: yes, with some rather obvious and formative changes. It has been tapped as the source material for the first resolved attempt at a Warhammer 40K show, and so I, a 40K novice at best, undertook reading the source material to see if this might be a show I’d like to give whichever streaming service picks it up money. An incredibly well-respected trilogy, graded on the curve required for licensed genre fiction, the books Xenos, Malleus, and Eisenhorn track story of the titular Inquisitor through and across much of the near-strangeness of the 40K setting. The exception, as cited from those inside and outside the fandom, is the Eisenhorn trilogy of novels by author Dan Abnett.

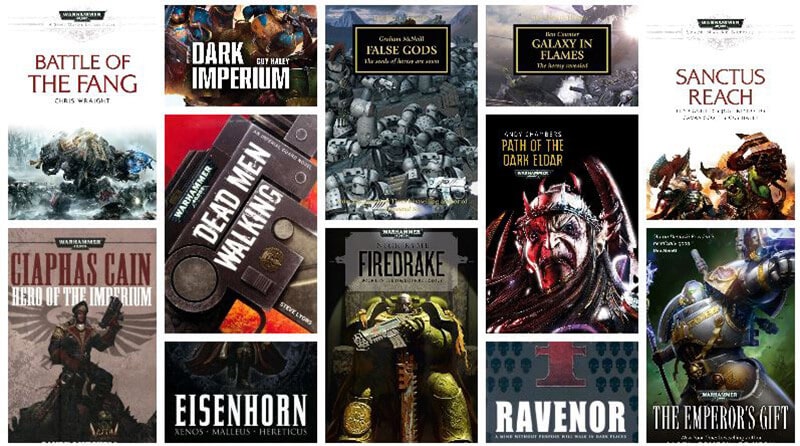

#Warhammer books isenhorn series#

And something you have to grapple with when it comes to the fictive universe of the Warhammer 40K setting is that to adapt most of its best narrative works is mainly to be adapting a series of video game cutscenes. In this format, you’ll be watching a vision presented to you by a group of professionals, from the writers to the directors to the crew to the cast. And even for the faithful, that particular flavor is a fun spice to drop on your tabletop game, but playing a game isn’t the same as watching a television show. You need a lot more people tuning in than have invested in miniatures to sustain an expansion into this market. Financially speaking, the people who love the Imperium of Man and all of its trappings, genuinely, and love the idea of grinning, hateful murder at the backend of history, in a future where there is only war - well, they don’t really sustain a streaming audience, probably. Morally speaking, well, we can’t speak to that, especially not under capitalism. So what do you do when the world comes back around the other way, and you’re sitting on a veritable IP gold mine, but fascism’s back and good god, but it loves irony? Much like a lot of British pop-counterculture at the time - 2000 AD, for instance, and Judge Dredd, and the work of Alan Moore and Grant Morrison and many, many others - they were a satire. The servants of the Emperor of Terra were originally something of a caricature of Catholic fascism, the Franco bent and its continental offspring that made its way, eventually, after some twists and turns, into British politics in the 1980s. This puts you in a bit of a pickle, both morally and financially.

What’s more, you want to make it about the factions that have been the protagonists of the setting since the intellectual property took off - the Space Marines, the Imperial Guard, the Inquisition humanity. So, you want to make a Warhammer 40K television show.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)